The problem is the strategy you design is rarely the strategy your teams execute.

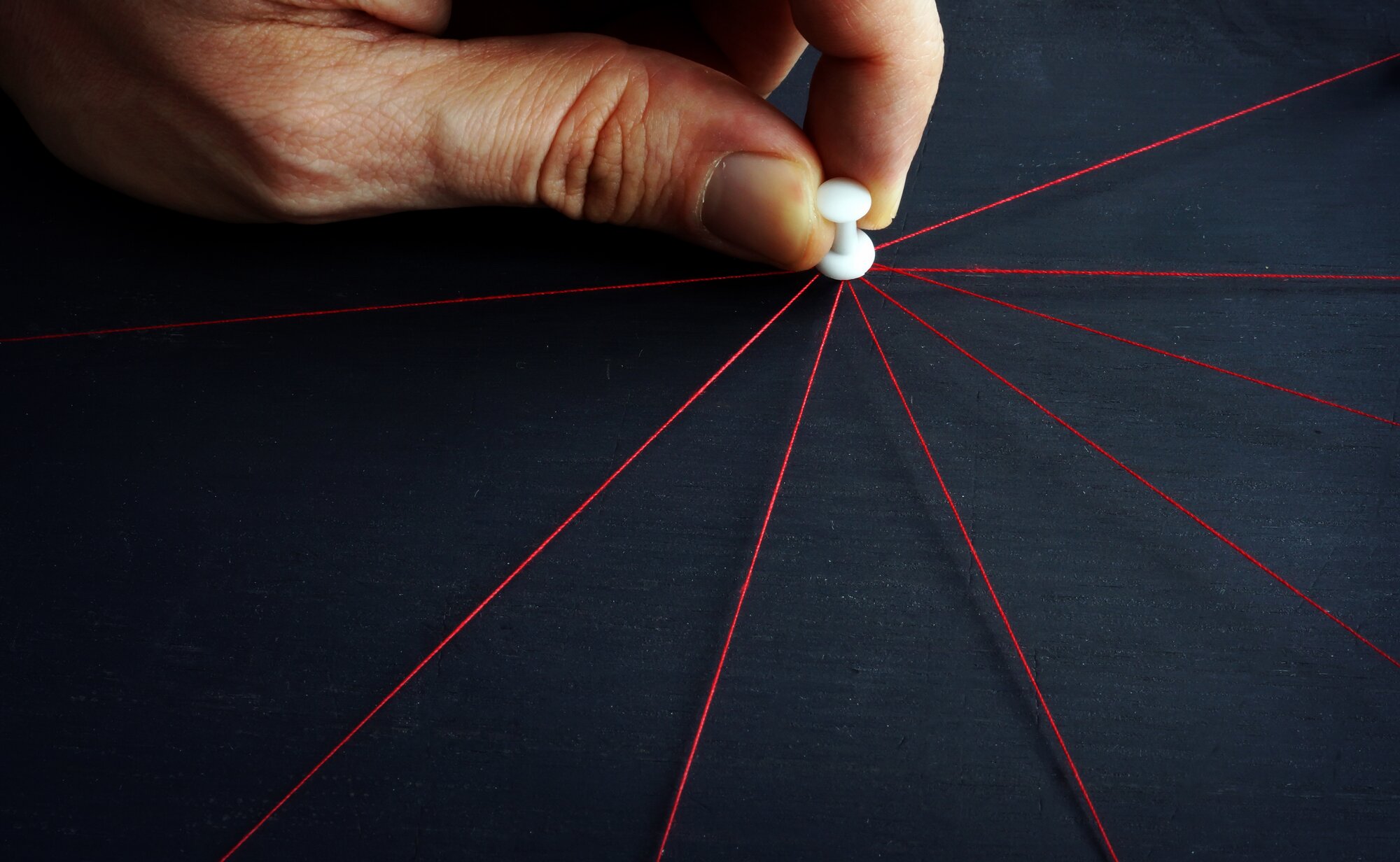

When strategy fails many teams think their strategy failed because execution was weak. But if you look closely, strategy almost never breaks in execution — it breaks in translation. Somewhere in the middle, the message bends just enough for the whole organisation to drift. Strategy is like light traveling through a lens, crystal clear at the top, bent just slightly in the middle, and landing in a completely different spot on the ground.

Every company has lived through this situation. Leadership shares a clear strategy, everyone nods, and everyone walks out of the room believing they understood the direction. But a few weeks later, when the work starts rolling in, the teams on the ground are moving in a direction that feels noticeably different from what was originally intended.

This disconnect doesn’t happen because people are careless or unwilling to follow the strategy. It happens because of something far subtler: the way mid-level managers absorb and interpret leadership messages before passing them on. They don’t repeat the strategy word-for-word. They translate it. And in that translation, small changes creep in.

Imagine leadership says, “This quarter, our priority is reliability. We want to reduce outages by 40%.” The intent is clear. But when a mid-level manager hears it, they might think, “Reliability is important, but we can’t afford to fall behind on features, or it’ll look like we’re slowing down.” So, when they share the message with their team, it comes out as: “We need to improve reliability, but let’s make sure it doesn’t delay feature delivery.”

Now the team is left confused. Which one matters more? Reliability? Features? Both equally? No one is trying to distort the strategy, yet it still ends up distorted.

This happens because mid-level managers operate under real pressure. They want to look aligned and decisive, avoid sounding unclear, and protect their teams from overwhelm. To manage all of this, they shorten the message, soften parts of it, remove the nuance, and add interpretations that make the strategy seem more manageable in their world.

But just like shrinking a photo makes it lose clarity, shrinking a strategy makes it lose meaning. What started as a sharp, high-definition vision becomes a blurrier version by the time it reaches execution.

That’s the core problem: strategy doesn’t fail during execution — it quietly breaks during interpretation.

Why interpretation errors in the middle quietly break strategy

At one of my earlier companies, leadership wanted to improve onboarding to support a major partner launch. The message was passed down as, “Fix onboarding issues.” Without the big picture, the team prioritised UI polish instead of the system bottlenecks causing churn. Everyone was busy, but the real problem remained untouched.

Research actually predicts this drift. Karl Weick’s Sensemaking Theory (1995) shows that people don’t act on raw strategy — they act on the version they construct in their own minds. Their past experiences, pressures, and assumptions quietly reshape the message before they ever pass it on. And Hansen & Haas (2001) found that as information travels through an organisation, people naturally compress it to keep things simple. But in that compression, nuance disappears — especially the why behind a decision.

This issue isn’t just theoretical. Gartner found that 60% of managers do not fully understand the strategy they’re responsible for executing. And Harvard data shows that only 29% of employees can correctly identify their company’s strategy at all. When clarity is this low, distortion is unavoidable.

This interpretation issue matters because even small shifts in interpretation can completely change what gets built, funded, and prioritised. Leaders may set a clear direction, but the version that teams actually execute is shaped by how mid-level managers make sense of it. And once the message bends in the middle, the entire organisation moves in the wrong direction, one small step at a time.

When strategies get compressed or softened, teams lose the “why” behind the decision. Without the real reason, they rely on assumptions. A strategy that was meant to create long-term impact turns into something that looks safer, smaller, or more familiar. Instead of solving the actual problem, teams end up solving a version of it that feels comfortable. This creates confusion, rework, and a lot of wasted energy.

For example, if leadership says, “We need to focus on reliability to prepare for big enterprise deals,” but the manager simply tells the team, “Fix reliability issues,” the team has lost the business context. Without knowing why reliability matters now, they may focus on the wrong areas—fixing minor bugs instead of hardening the core systems that enterprise customers care about. The intent was strategic, but the execution became tactical.

This becomes a real problem when it happens across multiple teams at the same time. Marketing may be pushing one message, product is building something slightly different, and engineering is solving a third version of the problem. Everyone feels busy, but nobody feels aligned. The organisation looks active on the surface, but the effort isn’t pushing in one direction.

Over time, this creates what many leaders experience but cannot fully describe: a slow drift between strategy and reality.

Projects don’t fail dramatically—they fade, lose momentum, or deliver half the impact they were meant to. The bigger risk is that leadership starts to believe execution is weak, when in reality the strategy everyone is executing isn’t the one leadership originally set.

And because these distortions are unintentional and invisible, they are almost impossible to catch once work has started. That’s why this problem matters: if you don’t manage the interpretation layer, you lose control of the strategy itself.

How to fix strategy distortion in the middle layer

Solving this problem doesn’t require more meetings, more slides, or more communication channels. In fact, those often make the distortion worse. What actually works is helping mid-level managers translate strategy with clarity, confidence, and honesty, instead of feeling pressured to simplify or “clean it up” before passing it on.

The first step is to create small sense-making moments right after leaders share a strategy. Instead of asking managers, “Do you understand?” ask them, “How do you interpret this?” When they explain the strategy in their own words, you can quickly spot where assumptions, confusion, or bias crept in. This prevents misalignment before it spreads.

Next, create a short reverse-briefing loop. Before managers take the strategy to their teams, ask them to summarise it back to leadership in two or three sentences. This simple practice reveals misunderstandings immediately. For example, a leader might say the strategy is about “long-term platform reliability,” but the manager might interpret it as “fix as many bugs as possible.” Catching this early saves week of drift.

Another helpful step is to make the hidden parts of strategy visible. Mid-level managers often compress messages because they’re afraid of overwhelming their teams or admitting they don’t have all the answers. By openly discussing trade-offs, uncertainties, and what is not the priority, leaders give managers permission to pass on the strategy in its real, honest form — not the polished, safe version.

You can also introduce a simple mental checklist for managers to use before communicating any strategic message:

- What did I add that wasn’t said?

- What did I remove to make this sound simpler?

- What am I unsure about but not saying out loud?

- What might my team misunderstand if I say it this way?

These small reflections reduce accidental distortion and increase clarity.

Finally, it helps to build a culture where managers don’t feel judged for asking tough questions. When leaders make it safe to say, “I’m not fully clear,” managers stop pretending to understand and start genuinely understanding. This single shift brings the whole organisation closer to the original strategic intent.

Solving strategy distortion is not about controlling the message — it’s about supporting the people who carry it. When the middle layer feels equipped, confident, and safe to ask questions, they transmit strategy in a sharper, more accurate form. And when the message stays clear, teams move faster, alignment stays tight, and the organisation builds what leadership actually imagined.

Try this with your team tomorrow:

- Ask each manager to explain the strategy back to you in one sentence.

- Ask where they feel uncertain — don’t let them hide ambiguity.

- Ask what not to do this quarter.

- Ask what trade-off feels most painful.

- Ask what they think their team will misunderstand.

What leverage this creates and why it matters for companies and teams

When the middle layer understands and communicates strategy with high accuracy, the entire organisation gains leverage that compounds over time. The biggest advantage is clarity. Clear strategy means fewer detours, fewer surprises, and far less wasted effort. Teams stop guessing what leadership truly meant and start building exactly what the company needs. This alone saves months of rework across a year.

The second major leverage is alignment. When managers pass down the same understanding — not five slightly different versions — every team pushes in the same direction. Product isn’t saying one thing, engineering another, and design a third. Instead of spending energy fixing confusion, teams spend energy delivering impact. This turns a company from a collection of busy groups into a coordinated system.

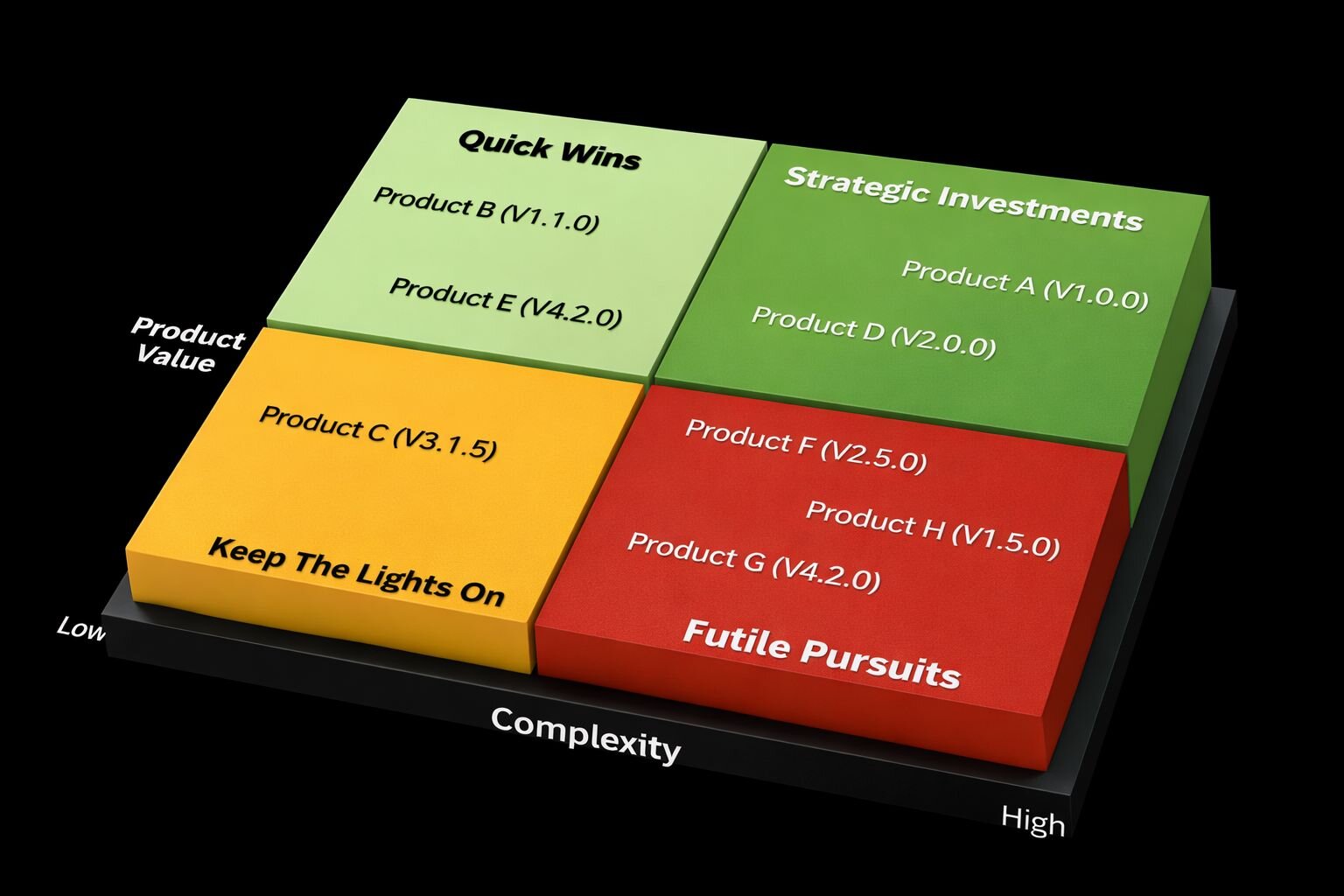

It also strengthens decision quality. When strategy is understood correctly, teams can say “no” with confidence. They can choose the right trade-offs because they know the real priorities. For example, if reliability truly is the top priority, teams won’t feel pressure to slip in scope, chase shiny features, or say yes out of fear. This leads to cleaner roadmaps, fewer rushed commitments, and simpler planning cycles.

Another important benefit is speed. Companies often move slowly not because execution is weak, but because strategy keeps getting interpreted differently. When the translation layer becomes strong, people spend less time debating direction and more time delivering. Meetings shorten, escalations decrease, and decisions happen faster because everyone is working from the same mental model.

It also improves trust up and down the organisation. Leadership starts trusting that their vision is being executed accurately, not diluted. Teams start trusting that managers aren’t hiding or reshaping messages. And managers feel more confident because they no longer carry the burden of “guessing what leadership really meant.” This creates a healthier, more open culture where information flows cleanly.

Over the long term, the company gains an even deeper advantage: strategic consistency. When strategies don’t drift during execution, long-term goals stay intact. Big bets get the focus they deserve. Transformation initiatives don’t lose momentum halfway. Companies stop oscillating between priorities because the message remains stable from top to bottom.

In simple words, by fixing the translation layer, you get a sharper organisation. Sharper organisations execute better. And better execution becomes a competitive edge.

This is the real value — not just fewer misunderstandings, but a company that moves with greater accuracy, coherence, and confidence every single day.

References

- Weick, Karl E. (1995) — Sensemaking in Organizations. Sage Publications.

- Explores how people interpret, reshape, and re-story information before acting on it.

- Hansen, Morten T. & Haas, Martine R. (2001) — Competing for Attention in Knowledge Markets. Administrative Science Quarterly.

- Shows how individuals compress and simplify information as it moves through complex organisations, losing nuance in the process.

- Gartner (2021) — Manager Effectiveness Report.

- Key finding: 60% of managers say they do not fully understand the strategy they are expected to execute.

- Kaplan, Robert S. & Norton, David P. (Harvard Business Review, 2015) — The Office of Strategy Management.

- Key statistic: Only 29% of employees can correctly identify their company’s overarching strategy.