If you work in product leadership right now, you are probably living in two realities.

First, the AI everywhere reality. Your CEO wants a generative AI story for the next board meeting. Sales wants AI on every slide. Competitors keep announcing assistants and agents that claim to automate entire workflows. The pressure to ship something AI-flavored is intense.

Second, the operational reality. Your day-to-day work looks very familiar. New users still drop out before activation. Onboarding flows still lose people. Integrations still break. The support queue is full of the same tickets as last quarter.

So the question for Heads of Product and Product VPs going into 2026 is not “Is AI real?”. It obviously is. The real question is:

How do you build an AI roadmap that survives scrutiny from your CFO and your future self?

We are moving from the experimentation phase of 2023–2024 into a return on investment phase. CFOs are looking harder at margins. The risk is no longer that you miss the AI boat. The risk is that you board a boat that burns cash with every user interaction.

This guide gives you a practical way to plan, budget, and execute AI initiatives that still make sense when the hype cools.

Part 1: The Case Study

The infinite cost trap

To understand the risks in AI product planning, it helps to look at teams that hit the unit economics wall first. One of the clearest examples comes from Latitude, the company behind AI Dungeon.

Based on public reporting and interviews, here is what happened, translated into product terms.

The vision

AI Dungeon launched as a text adventure game where every story was generated on the fly by a large language model. Unlike a traditional game with fixed content, AI Dungeon used models from OpenAI to create new scenes and dialogue for every player, every time.

From a product perspective, this looked perfect: high engagement, endless content, no writers to pay.

The mechanism

Under the surface, the cost model was very different from normal software.

Large language models do not have memory in the usual sense. To generate the next line, they need to see enough of the previous story as input each time. That input is billed in tokens.

As a player’s story grew longer, the number of tokens the model had to read and write for each turn grew as well. In practice, the heaviest users created the highest costs, because they produced long, detailed stories that the system had to reprocess repeatedly.

The crisis

Because Latitude was using a third-party API and paying per token, every action in the game had a real cost. As usage grew, so did the bill.

Reports at the time described monthly AI costs climbing into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. In other words, the business was effectively subsidizing its most loyal users to the point where success became dangerous. The more people played and the longer their stories, the worse the unit economics looked.

The pivot

To survive, Latitude shifted to a more flexible, model-agnostic setup. They reduced dependence on a single expensive provider, brought in cheaper models for many turns, and reserved premium models for moments where quality mattered most. Architecturally, that meant adding layers between the game and the models so they could switch and mix providers.

The core lesson is simple: they had built a product where value to the user and cost to the company were no longer aligned. It took a major rework to fix that.

The B2B parallel

You might think this is just a gaming story. It is not.

Consider a hypothetical SaaS platform, “DashCorp”. In 2024, they launch a “Chat with your data” feature powered by a top-tier model. Users can ask questions like “Summarize our last five years of sales by region and product line”.

To drive adoption, DashCorp bundles this into their 30 dollars per user per month plan at no extra cost.

Most users ask small questions. A few power users start pasting giant CSV exports into the chat. For a subset of accounts, the AI feature now costs roughly 40 dollars per month per heavy user in model and retrieval costs, while those users are still paying 30 dollars for the whole product.

On the surface, the feature looks like a win. Engagement is high, demos look great, and customers are happy. Underneath, the margin picture is getting steadily worse.

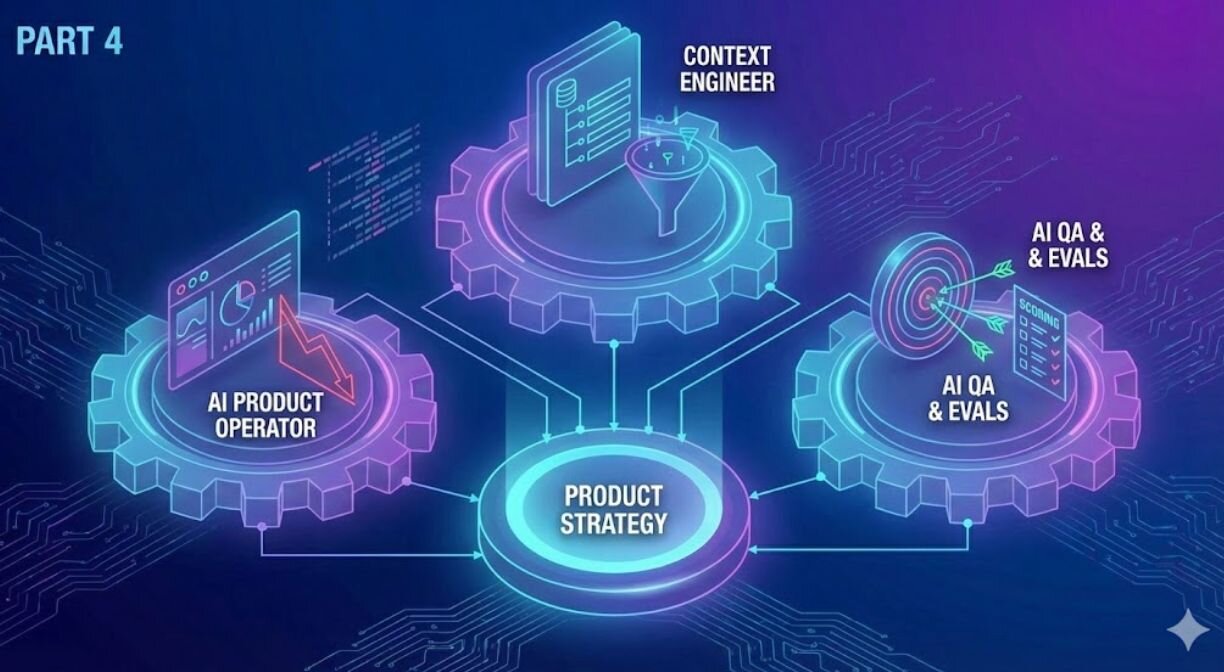

The 2026 takeaway

Many product teams are quietly building AI Dungeon-style mistakes into their B2B roadmaps.

They are wiring variable cost engines, like large language models and retrieval pipelines, into products that are sold on fixed subscription prices. Without usage caps, smart routing, and clear economics, the very users who love the feature most can become the ones who quietly erase your margin.

Part 2: The 2026 budgeting framework

Modeling the cost of thought

Traditional SaaS economics assume that once you build the feature, the marginal cost of an extra click is close to zero. AI changes that. Every query has a cost.

For 2026 planning, you need to pull AI out of the generic “R&D” bucket and think about an AI profit and loss line. That means understanding three things.

1. Margin dilution is real

Several productivity and collaboration tools have discovered that AI features can lift revenue and engagement while putting pressure on gross margins. When heavy usage drives up model and infrastructure costs, top-line growth can mask underlying erosion in unit economics.

In an environment where investors and finance leaders care more about sustainable margin than flashy demos, that is a problem.

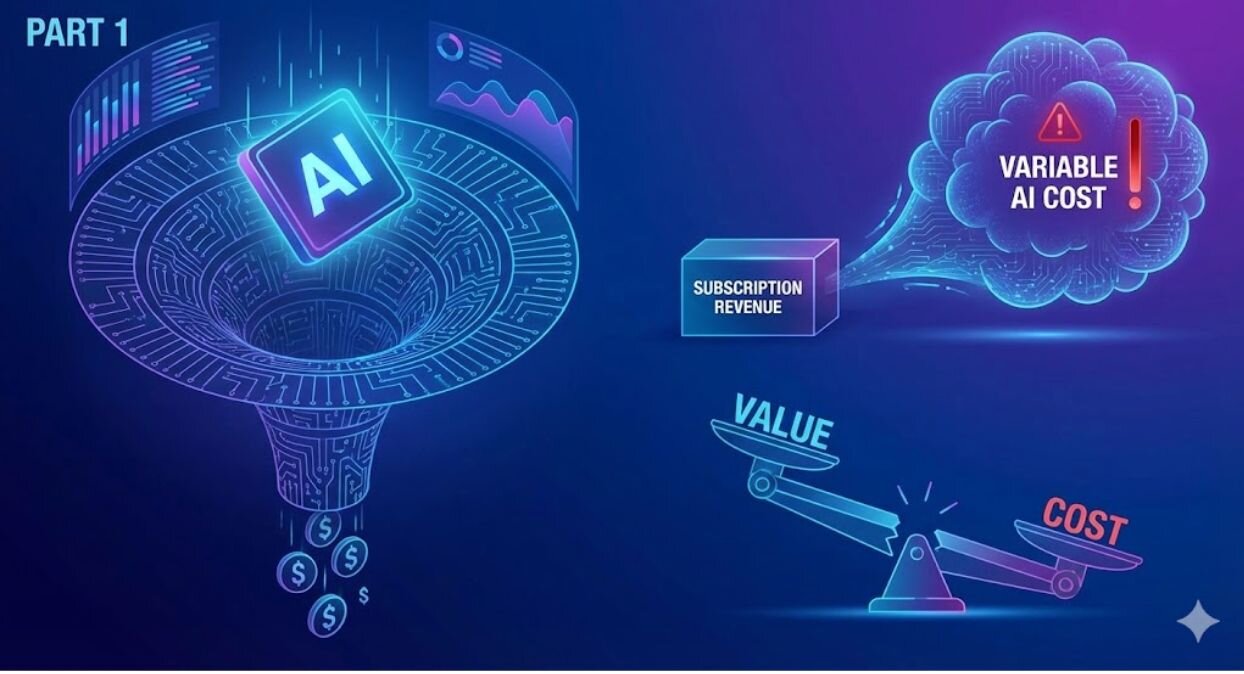

2. A new COGS equation

When you defend your budget to a CFO, you need a simple way to explain the cost side of AI features. One practical way is to think in three buckets:

- Input cost: the tokens you send to the model. That includes the user’s question and any context or documents you attach.

- Output cost: the tokens the model generates in its answer.

- Retrieval cost: the cost of your vector database or search layer, which finds relevant documents or facts to include.

In plain terms, long prompts, large context, and verbose answers all cost money. Features that encourage “just ask anything, paste anything” can create cost patterns that are hard to predict and defend.

3. The 3x rule

To bring discipline into the roadmap, apply a simple rule of thumb in planning:

An AI feature should create measurable value at least three times greater than its direct compute cost.

If a single run of an automated invoice review costs 15 cents in compute and retrieval, you should be able to make a credible case that it saves the user at least 45 cents worth of time or reduces risk by a similar amount. If you cannot, treat the feature as research or brand marketing, not as a core product.

4. Circuit breakers for agents

As teams move toward multi-step agents that plan, act, and retry, the risk of runaway loops increases. An agent that gets stuck can call the model repeatedly and hammer your retrieval systems in the process.

From a budget perspective, you need protection. That protection looks like circuit breakers: hard limits on how many steps, how many model calls, or how much spend a single agent run is allowed to consume before it stops and falls back to a simple, understandable path.

In practice, that might mean: if an individual task for an agent crosses a set cost threshold or step count, stop the automation, surface partial progress to the user, and ask them how to proceed.

Part 3: The planning toolkit

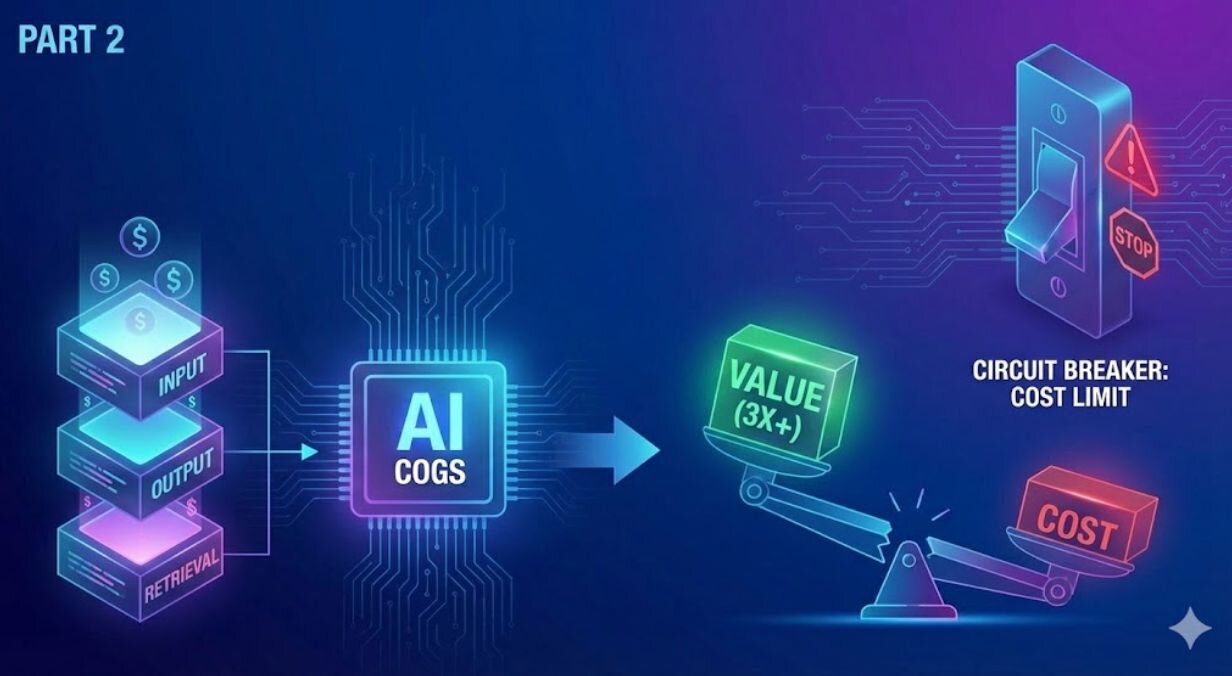

Four filters for your 2026 roadmap

With that context, the job of product leadership is to decide which AI work belongs on the roadmap, which belongs in experiments, and which does not belong at all. The following four filters are a practical way to do that in planning sessions.

Filter 1: Problem first, AI second

Many weak AI features are technology-first. They were born as “we should add a copilot” rather than “we should fix this painful user problem”.

In workshops, insist that every proposed AI feature starts with a description of how users solve the problem today.

For example:

- Baseline: “A customer success manager exports account data into Excel, writes formulas, and builds a pivot table to understand churn risk.”

- AI target: “They type or select a question inside the product and get a chart or narrative answer that is good enough to use immediately.”

Once the baseline and target behavior are clear, define a specific outcome such as “time to insight drops from 15 minutes to under 1 minute for this persona” or “support tickets on this topic drop by 30 percent”. If teams cannot describe both, the idea is not ready.

Filter 2: Reversibility and model agnosticism

The AI model landscape is changing quickly. A model that feels premium today may feel average next year. Costs and capabilities will keep shifting.

Your product should not be tightly coupled to any single provider’s quirks. Instead, treat model providers more like utilities: important, but replaceable.

Architecturally, that usually means adding an orchestration layer between your user experience and the models. This layer owns routing logic, prompt templates, and provider configuration. It lets you send simple tasks like classification or routing to cheaper models and keep more demanding tasks, such as complex reasoning, on more capable models.

As a product leader, when you review technical designs, ask simple questions:

- Where do prompts and system instructions live, and who can change them?

- If we wanted to test another model next quarter, could we do it with configuration and small changes, or would we have to rewrite flows?

- Are we mixing models based on cost and quality, or sending everything to the same expensive option?

You do not need to design the architecture yourself, but you do need to enforce reversibility as a requirement.

Filter 3: Clear kill criteria

AI features have a running cost. That makes “zombie features” more expensive than usual. You cannot afford to keep underperforming features alive just because they are impressive in demos.

Before you build, agree on a small set of failure conditions for each non-trivial AI feature. For example:

- If negative feedback on answers stays above a certain rate for two or three review cycles.

- If the average latency for key flows remains above an acceptable threshold.

- If the cost per active user for the feature exceeds a set fraction of that user’s subscription value.

If the feature hits those conditions and you cannot see a realistic path to improvement, remove it or dramatically reduce its scope. In a tight margin world, “delete” is a valid and sometimes necessary product decision.

Filter 4: Success is defined as less manual work

In 2024, many teams defined AI success as “percentage of users who clicked the AI button”. That was understandable in the experimentation phase, but it is not enough for 2026.

Your measures of success need to be closer to real work. For example:

- “Reduce time to complete onboarding task X by 40 percent using AI guidance.”

- “Reduce tier 1 support tickets about basic how-to questions by 30 percent using an AI assistant.”

- “Increase the share of invoices approved without human intervention by 20 percent with AI checks.”

Even your objectives and key results should reflect that. Instead of “50 percent of weekly active users try the AI assistant”, aim for “customers who use the assistant open 30 percent fewer how-to tickets than those who do not”.

This does not mean usage metrics are useless, but they should support, not replace, measures that track whether users actually stop doing manual work.

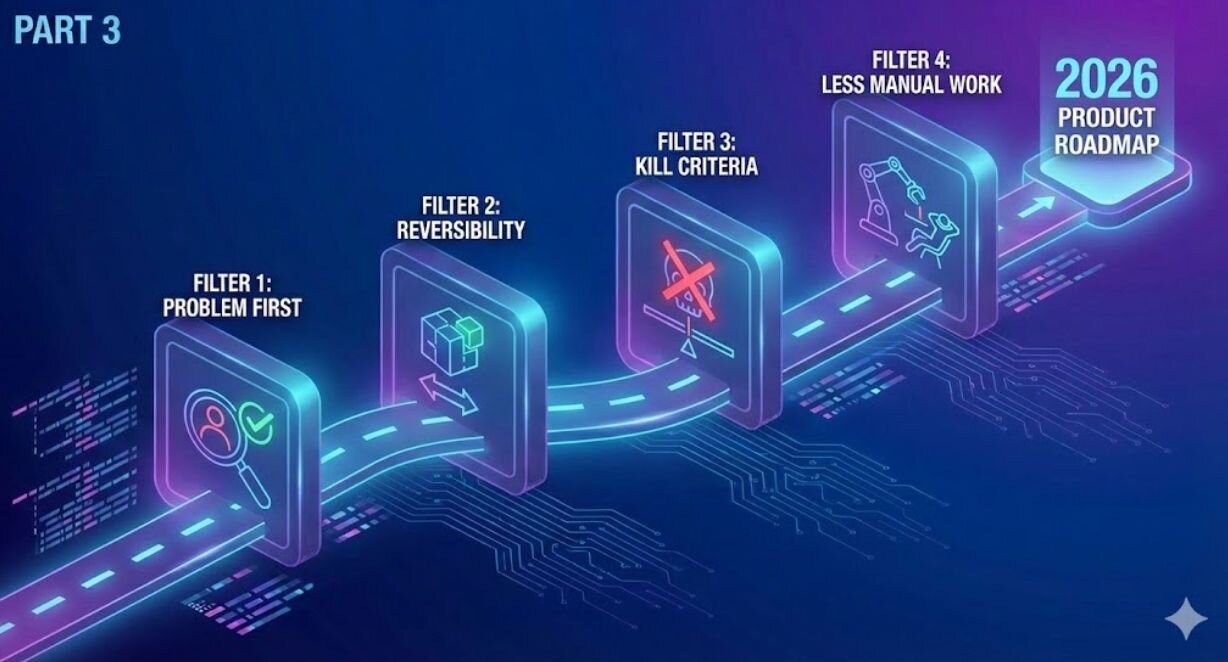

Part 4: Upskilling your product organisation

New responsibilities for the AI era

You do not need to replace your product managers with machine learning specialists to build good AI products. You do need some new responsibilities covered, whether as distinct roles or as part of existing ones.

1. The AI product operator

This person may sit in product, product operations, or analytics. Their job is to make the unit economics of AI features visible.

They own dashboards that tie together feature usage, token and infrastructure spend, and business value. They are the first to spot when a particular segment, workflow, or customer is driving outsized cost without matching benefit. They are also the ones who can walk into a roadmap review and say “this feature is popular, but it is marginally negative unless we change something”.

2. The context engineer

Generative systems do not just respond to prompts. They respond to whatever context you give them: documents, help content, product data. If that context is messy or stale, the results will be poor, regardless of how good the core model is.

The context engineer owns the retrieval part of the system. That includes deciding which data sources are used, structuring them so they are easy to search, keeping them updated, and working with domain teams to remove or flag outdated content.

In many organisations, this responsibility might sit with a technically inclined product person, a data engineer, or a platform engineer, but someone needs to wake up in the morning thinking about context quality, not just model choice.

Traditional quality assurance is binary: given input A, the system should produce output B. If it does, tests pass.

AI output is probabilistic. The same input can yield slightly different answers, and what matters is whether the answers are good enough, not whether they are identical.

To handle this, teams are moving toward evaluation sets, often called evals. These are collections of realistic questions or tasks, each paired with an example of an acceptable answer or outcome. The system runs through these regularly and scores itself, so you can see whether quality is improving or regressing as you change prompts, models, or retrieval.

Someone in your organisation should be responsible for designing and maintaining these evals, interpreting results, and feeding that back into product decisions.

Crucially, all three responsibilities tie back to planning and budget. Without them, you are steering blind.

Conclusion: The Latitude test

The public AI market will almost certainly cool. The press will move on to the next story. Some vendors will disappear or consolidate. Compute prices and capabilities will shift again.

What will remain is the simple fact that using machine learning in your product has a real cost and a real benefit. The teams that win will be the ones that treat AI as a powerful but expensive raw material and manage it with the same discipline they apply to infrastructure and people, not as a magic trick.

One simple exercise for your next roadmap review:

Take your top three proposed AI features and run the Latitude test.

Ask: If a heavy user runs this feature 100 times a day, does our margin on that user go up or down?

If the answer is down and you do not have a convincing plan to change that, treat the idea as unfinished. Send it back for redesign or back into the experiment bucket.

Your job as a product leader is not just to put AI into the product. It is to build products that scale in value faster than they scale in cost.

Keep reading

Designing safe conversational AI: The risks product managers overlook

Surviving the perfect storm: How hardware PMs can beat the AI tax and trade tariffs

From repetitive work to real impact: A case study on building an AI recommendation for developers

Product managers' role in making AI/ML systems more relevant