Climate and EnergyTech fail in far more ordinary (and far more revealing) ways than people expect. From the outside, it’s easy to assume the hardest challenges are purely technical: long-duration storage, grid optimization, or emissions modelling. But inside the industry, a different pattern appears. Prototypes perform well, pilots look promising, and yet the product never becomes part of day-to-day operations.

The failure point is rarely the innovation. Climate and EnergyTech don’t collapse at the moment of invention. They collapse when the invention meets the conditions into which it has to fit. Navigating those conditions, that is, interpreting them early enough to influence the shape of the product, is where product managers in Climate and EnergyTech end up spending most of their time. And in my work, this is exactly the space where I operate, making sure what we design can actually survive the realities of deployment.

How climate & energyTech products meet the real world

For all the ambition around decarbonisation and grid modernisation, most adoption barriers in Climate and EnergyTech are procedural, infrastructural, or regulatory, or rooted in how data is collected and formatted. The first cracks usually appear in the assumptions teams don’t question, and it is something I notice quickly because I came into the product through QA and security testing. You learn to look for the places where a system will fail under real conditions, not ideal ones.

One energy-sharing feature we built assumed sub-minute load data because the optimization engine benefited from it. A customer workshop revealed their meters still produced 15-minute intervals, and some of their rooftop PV sites exported CSVs overnight via secure mailbox. We reworked the feature for the data resolution the grid actually provided, not the one the optimization logic preferred.

In another case, a demand-response alert fired exactly where the product’s optimization engine predicted it had the highest economic value. Operators explained that this fell during their shift handover – a period when no one initiates new dispatch decisions. Again, a test mindset helps: you stop looking at how the code behaves in isolation and start looking at how the system behaves under actual workloads. Adjusting the logic to match the rhythm of real control rooms made the feature usable.

Sometimes the constraint is regulatory rather than technical. A forecasting component originally stored a sensor attribute to improve accuracy. But storing it would have placed the utility under a stricter NIS2 classification, triggering requirements they weren’t equipped to audit. We rebuilt the calculation so the value was processed in-memory and discarded. The insight remained; the compliance burden disappeared.

None of these adjustments was glamorous, but all of them were decisive. They determined whether the product could move forward at all.

Why do these problems appear

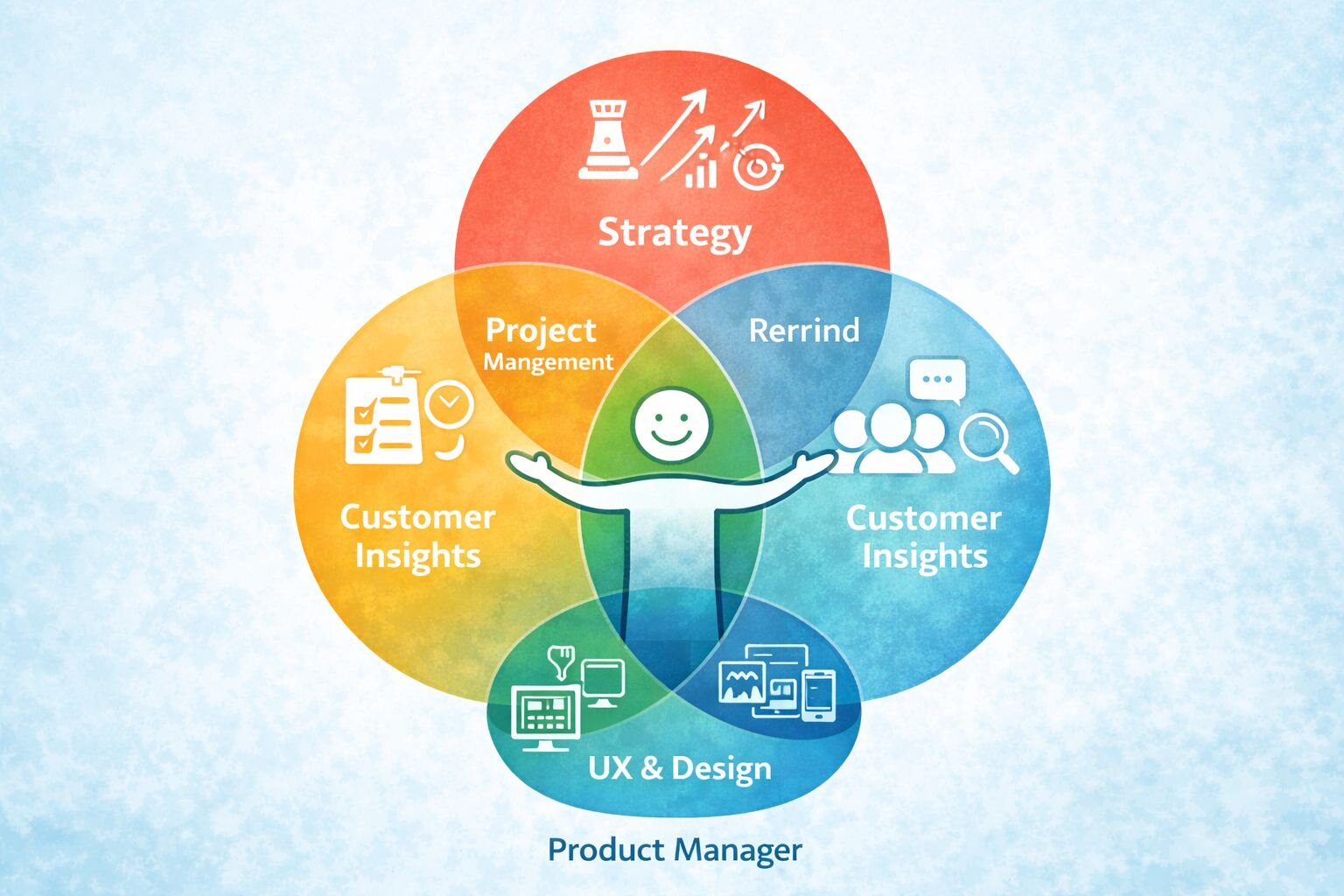

These examples aren’t bugs. They’re symptoms of a deeper disconnect: the product works in isolation, but every team around it evaluates it through a completely different language. And once you recognize that, it becomes obvious why so many Climate and EnergyTech products get stuck: three distinct perspectives rarely converge on their own.

Engineering works from what the energy system should provide: sub-minute telemetry for distributed-energy resources (DER) optimization, stable imbalance prices from the market operator, or the ability to automate dispatch actions. They hit friction when customers still run half their fleet on 15-minute meters or when automation isn’t allowed without a human confirmation step, no matter how reliable the algorithm is.

Investors look at a different set of bottlenecks: whether a flexibility pilot will stall behind a Distribution System Operator’s (DSO) seasonal freeze on changes to operational systems, whether revenue depends on a capacity-market tender that only opens twice a year, or whether a feature hinges on a regulatory interpretation, like EU Taxonomy, ISO 14064, or FERC Order 2222, that may shift.

Operators and end users focus on the practicalities of running energy assets and staying compliant: whether an alert lands outside dispatch windows, whether an emissions calculation matches their auditor’s template, whether the tool reflects specific grid codes, or whether it requires data their asset-management system can’t export. For them, a feature that disrupts established workflows is more costly than one that is merely technically imperfect.

No group is wrong about their concerns. They’re simply anchored in different parts of the system.

What makes this even harder is that, in Climate and EnergyTech, these constraints rarely surface early. Most of the critical information about infrastructure limits, regulatory requirements, or operational boundaries only emerges once the product is already in motion. Over the years, I’ve learned that a big part of my role is simply uncovering these hidden constraints early enough to prevent the product from drifting toward a dead end.

Where the product manager can actually change the trajectory

In Climate and EnergyTech, a product manager’s impact appears in small but pivotal corrections. These corrections might look tactical, but they follow a consistent pattern. Each one comes from translating a specific kind of mismatch in the system: between product assumptions and operations, between regulation and implementation, or between stakeholder expectations and design.

1. Translating product assumptions into operational realities

Many product dead ends start with optimistic assumptions buried deep in the product’s internal logic. I’ve redirected engineering work that relied on Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) upgrades a utility wouldn’t install until the next fiscal year, preventing weeks of development that would never be deployed. I’ve kept pilots alive by routing through an existing read-only SCADA endpoint instead of waiting months for a full integration that the customer wasn’t ready to approve. None of these choices was elegant. All of them moved the product forward because they recognized the operational world the product needed to run.

Hardware adds another layer to this translation work. In EnergyTech, prototypes are rarely just software: you often depend on physical components such as sensors, batteries, inverters, or even experimental fuels. That means assumptions about how a device behaves cannot be validated with code alone; they require manufacturing, testing, certification, and safety approvals. Even a small mismatch between what the product expects and what the hardware can deliver can introduce months of delay. This makes it even more important to confront optimistic assumptions early.

2. Translating regulatory ambiguity into workable product boundaries

Regulation in energy systems isn’t an afterthought. It is architecture. We once planned to store a sensor attribute that would have triggered a stricter operational-technology security classification inside the utility. Instead of escalating into a months-long legal review, we reworked the component to calculate in-memory and discard the value. These decisions aren’t about avoiding regulation; they’re about building features in ways that keep deployment pathways open.

3. Translating stakeholder friction into meaningful design constraints

Engineering optimizes for correctness. Investors optimize for timing and revenue. Operators optimize for stability. When we realized an emissions-reporting update would only be reviewed during the customer’s annual audit window, we delivered adjacent functionality instead of letting the project sit idle for months. These interventions come from converting competing expectations into practical constraints that the product can work within.

Together, these translations form the actual work of product management in Climate and EnergyTech: spotting inflection points early and steering the product toward the paths that the system can support. In this industry, progress doesn’t come from perfect features; it comes from features shaped around constraints that won’t change fast enough.

Final words

ClimateTech’s next decade will be defined by a simple reality: the bottleneck is no longer algorithms, but alignment. Markets, regulators, DSOs, and asset operators are shaping the conditions for adoption faster than technology teams expect. Products that can adapt to these forces will scale; those that ignore them will fade.

We’ll see three major shifts:

1. Regulatory-aware design will become a competitive advantage.

GDPR classifications, EU AI Act obligations, grid-code logic, and audit requirements will increasingly shape product architecture.

2. Operational compatibility will beat theoretical optimization.

Time-based data resolutions, manual overrides, safety interlocks, and human-in-the-loop dispatch will continue to define real deployments.

3. Translation skills will become the difference between growth and stagnation.

The companies that dominate the next phase will be the ones whose product managers can interpret ambiguity by turning regulatory, operational, and market constraints into usable pathways.

ClimateTech will scale through products built for the infrastructure and institutions that exist today. The future belongs to teams who understand the system they’re entering, and to the translators who can turn that understanding into design.