When people talk about building software, the stories often focus on the elegance of the code, the cleverness of the interface, or the speed with which a team brought a feature to market. In enterprise SaaS, the reality is far more complex. Here, success isn’t defined by how quickly you can release something, but by whether your product can survive the gauntlet of procurement, compliance, and scale.

On paper, the product strategies might look just right: restructured processes, clean execution plans, and technology recommendations that mapped neatly to business goals. But in practice, most of those strategies struggle under the weight of messy systems, conflicting priorities, and political realities. It became clear to me that the gap between “what should happen” and “what actually happens” was enormous - and that gap was where business value was often lost.

That realization is what pulled me toward product management at SqlDBM. For me it was a chance to sit at the intersection of business strategy and technical execution. Instead of handing over slides that said what should be done, I could take responsibility for building the thing that made it possible. Over the last three years, that shift has meant bringing several different enterprise SaaS products to market: some became standout successes, others not.

What those experiences taught me is that enterprise SaaS plays by different rules than consumer tech or even SMB software. Enterprises don’t buy features - they buy risk reduction, compliance, and time savings. They care about whether your product can integrate into their existing stack without disruption, whether it helps them pass audits, and whether it makes their teams more efficient without adding complexity.

That is why building enterprise SaaS requires a fundamentally different mindset. You cannot afford to assume you know what matters; you must validate it through structured pilots and willingness-to-pay signals. You cannot ignore security and governance until later; those are table stakes from day one. And you cannot wait for perfection; enterprises reward relevance, not polish.

The story I want to share is not one of flawless execution, but of experiments, course corrections, and lessons learned. Some of those lessons came from the products that worked, with examples: Model Governance, Global Standards, and Global Modeling. Others came from the ones that didn’t. But taken together, they paint a clear picture: the companies that win in enterprise SaaS are not the ones with the flashiest features, but the ones that learn fastest, validate with revenue, and design for the realities of enterprise life.

What Worked: Patterns Behind the Winners

When I look back at the three products that stood out as genuine successes, what strikes me most is how consistent the underlying patterns were. The products themselves were different - Model Governance added an extra layer of description and control to modeling space; Global Standards unified naming, conventions, and patterns across the whole organization; Global Modeling enabled a cross-project linking that correlates to different databases working together. Yet the way we arrived at those wins followed a repeatable rhythm. It wasn’t luck. It was a combination of disciplined discovery, structured validation, creative reuse of capabilities, and an intentional strategy to build momentum.

The first and most important pattern was how we approached customer discovery. Too many product teams start with assumptions: they think they know the problem, they think they know the pain points, and they assume that what excites them will excite customers. We did the opposite. For every product that worked, we began with conversations, not features. These weren’t casual chats. They were structured interviews focused on understanding the job the customer was trying to get done, the moments when their process broke down, and the metrics they cared about. When some data engineering managers told us approval processes were taking weeks and exposing them to compliance risk, we knew we were dealing with a problem worth solving.

Discovery alone, however, wasn’t enough. The second pattern was validation before code. We built design partner programs where customers agreed to test prototypes, provide structured feedback, and participate in pilots with explicit success criteria. In one case for Global Modeling, we created a lightweight mock-up that illustrated how a standardized component library could reduce modeling time and variation. Customers didn’t just nod politely - they leaned forward and asked when they could get their hands on it. That moment was worth more than any internal enthusiasm. And when procurement teams later fought to extend the pilot beyond the initial trial window, we knew we had moved from curiosity to conviction.

The third pattern was repurposing. Innovation is often imagined as inventing something completely new, but in practice, some of our most impactful features came from asking, “What else can we do with what we already have?” The diff engine we had originally built to track schema changes became the backbone of our impact analysis product. The approval flow we designed for internal governance was adapted into a customer-facing workflow that helped entire organizations manage compliance. By treating our platform capabilities as modular building blocks, we were able to deliver high-value solutions without overextending engineering.

Finally, three magic letters: M.V.P. Every roadmap needs quick wins - small, visible improvements that deliver immediate value. The first link in this chain is an MVP: something that can start bringing value day one, despite not being polished or functionally complete. The Global Modeling MVP shipped with a single approval gate, minimal audit trail, and one warehouse integration - just enough for data engineers to try real changes and for managers to see approval cycle time move. MVP reduces the risk of going in the wrong direction and helps you pivot earlier if needed.

During the implementation of our successful features, we noticed that change failure rate (CFR) fell below 20%, which means that we had to rework less by discussing more beforehand. Feature adoption grew faster due to higher engagement with the clients even before the feature was ready. Time to approval was shrinking since we saw the real need from the clients and therefore didn’t spend too much time.

Taken together, these patterns formed the backbone of our three biggest successes. They weren’t glamorous processes, and they required patience and discipline. But they worked because they aligned our efforts with real enterprise pain points, eliminated assumptions, and gave customers tangible value quickly.

What Didn’t Work: Root Causes, Not Symptoms

If the three wins had clear, repeatable patterns, the products that struggled revealed an equally consistent set of pitfalls. These weren’t random missteps. They were avoidable traps - patterns of thinking that can easily seduce a product team, especially in the enterprise SaaS world.

The first and most dangerous trap was building from assumptions. There were moments when we convinced ourselves that we knew what the customer needed. We had internal champions and we had our own strong opinions. But what we didn’t have was external validation. That led to features that were technically great, had fantastic functionality, but ultimately irrelevant because they addressed problems too minor to matter. Customers used them occasionally but never fought to keep them. Alternatively clients were willing to use but not willing to pay, since the product was solving not the pain point but some inconveniences, users could live with.

The second trap was internal hype. At times, enthusiasm inside the company became a substitute for evidence outside it. A product leader might describe a feature as “game-changing,” or a development team might get excited about a new capability. It felt good, it created momentum, and it encouraged us to push forward - but enthusiasm without proof from the market is just noise. At this step companies might get too excited and start building product to have a product, not to solve clients problems.

Another recurring challenge was underestimating scope. It is one of the most commonly seen problems in product companies, not necessarily SAAS. In consumer products, you can sometimes get away with a lean first version and add polish later. In enterprise SaaS, especially in data management, that luxury doesn’t exist. A feature without proper integrations, SSO, audit logs, and compliance considerations isn’t half a product - and it might be unusable at all. A huge challenge here is to find the right balance between MVP and an enterprise-grade product. Some companies will not talk to you before all the functionalities, especially security-related, are in place. Others are less demanding and can help validate the product before finishing everything, but with clear vision that promised pieces will be delivered. But even in this case it is pretty easy to underestimate time and effort, required to build this simplified version.

We also underestimated the go-to-market efforts required. Building the feature is only half the battle. Assuming that product will self itself is a suicide. Maybe not, but only if you can wait for months before the first sale and years before you hit your sales goals. In some cases hype and market can solve this problem for you, as we see it with AI nowadays, but I haven’t seen any enterprise SAAS product that was launched without proper GTM and succeeded. Go to market is not only a marketing budget, it is a complex undertaking that requires close collaboration between product, sales, and marketing teams. It should start before even the first line of code is written. And continues till first sale, after that it is just scalability.

Finally, there was perfectionism. Too often, we delayed releasing a product until it felt polished enough or had “enough” of functionality. We wanted the interface to be seamless, the workflows to be flawless, the edge cases to be fully covered. We said to ourselves that no one will buy it until we have this or that feature, or if we haven’t made it perfectly bugless. In reality, customers would have preferred a rougher version that solved a critical pain point immediately. By waiting too long, we slowed our learning cycles and denied ourselves the opportunity to correct the direction earlier. I already mentioned an MVP earlier, but here it is more about trying to make a product that suits everyone, that checks all the boxes. From my experience, it is absolutely impossible to satisfy everyone.

Looking back, these weren’t tactical mistakes; they were root causes. We assumed instead of validating. We confused internal energy with market demand. We treated go-to-market as a handoff instead of a continuation of the product journey. And we equated polish with readiness. Each of those patterns eroded the effectiveness of our products, and they serve as reminders that in enterprise SaaS, the margin for error is narrower than most people realize.

The framework

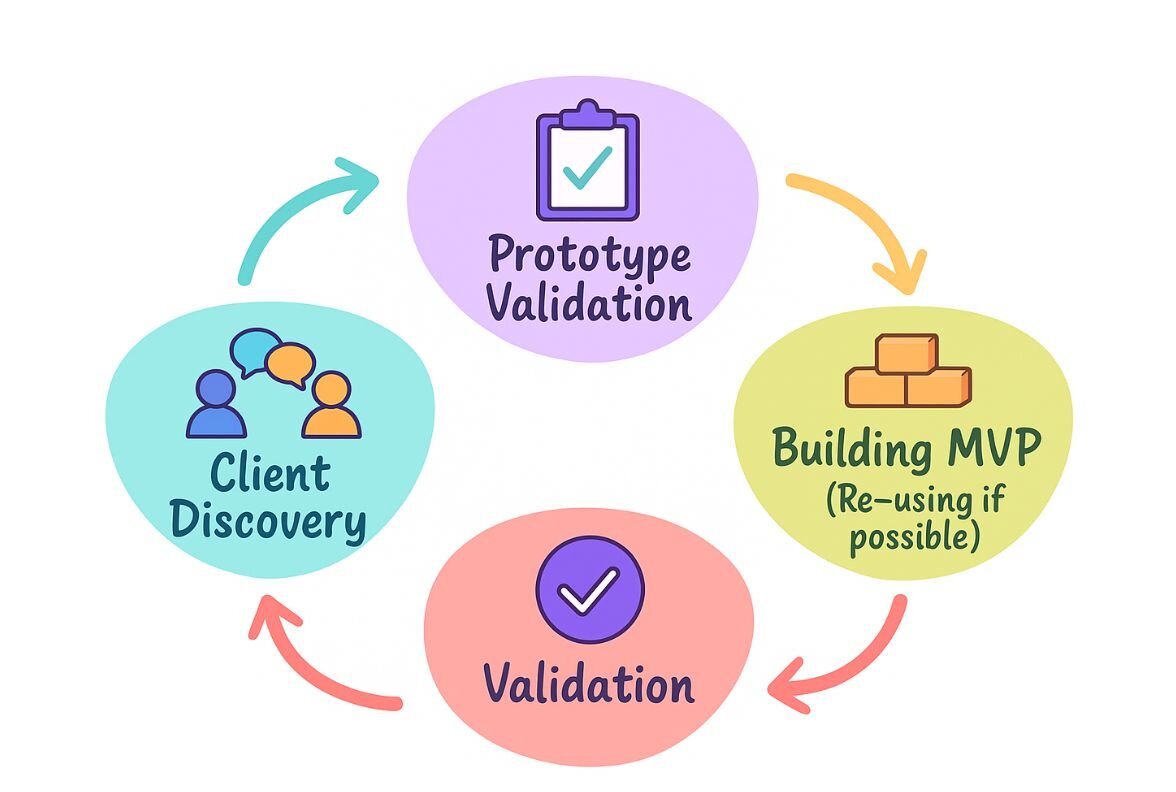

I built a simple but working framework for my next product. It is extremely simple - validate before build, build small, validate again, sell. Each of these simple steps include enormous effort from different teams - product, engineering, sales, and marketing. But it will ensure positive ROI and overall customer satisfaction.

Everything should begin with the idea. Not the idea of the product itself but the idea of the problem we are trying to solve. We should ask ourselves: are we solving a pain already articulated by data architects, data engineers, or their managers or are we trying to invent the problem first? If we have a clear understanding of customers’ pain and a high level idea how to solve it, move to the next step.

The next step is prototyping. Today, this is extremely simplified with AI coding tools that can build decent prototypes in minutes. And then - validation. Internal, with product champion, and external with trusted clients. A prototype can also help with outlining MVP boundaries, showing clients what exactly we will deliver at first, but giving enough space for improvements.

Finally, it is time for the MVP. In the past, we might wait too long, polish features or over-engineer scope before customers ever touched the product. Today, I would insist on shipping something tangible within weeks, not months. The MVP wouldn’t be a rough sketch, though; it would be a thin but functional slice of the product that customers could actually use. It might only solve one job, but it would do so end-to-end, with enough underlying functionality, basic integrations, and minimal governance, so that enterprise users could evaluate it seriously. The goal is not polish but proof: proof that the problem is sharp enough, proof that customers are willing to adapt workflows, and proof that the value is visible.

Another validation principle is monetization from day one. It’s easy to treat early pilots as free experiments, but free usage doesn’t validate willingness to pay. What matters in enterprise SaaS is whether the solution reduces risk or saves time enough to earn a budget line. That doesn’t mean charging Fortune 500 clients full freight for a prototype. It means structuring pilots so that there is an explicit commercial component - whether through paid pilots, tiered access, or add-on fees. Revenue is not just the outcome of validation; it is a form of validation itself.

Next, I would adopt a dual-track tactics: discovery and delivery running in parallel, continuously. In some of our launches, discovery was front-loaded: we did interviews, defined requirements, then shifted focus entirely to building. That approach assumes the world stops moving once development begins. In reality, customer needs evolve, competitive landscapes shift, and assumptions decay quickly. A dual-track approach means the team is always learning while building, always testing hypotheses with customers while shipping incremental value. This process reduces the risk of drift and ensures that the roadmap stays aligned with validated demand.

Finally, I would connect every product decision with structured pilot projects with clear expectations. Sometimes in the past, pilots drifted into side projects - still running, still consuming resources, but not delivering decisive evidence one way or another. Today, I would set pilots up like contracts: here are the outcomes we’re testing, here’s how long we’ll run, and here’s what success or failure looks like. At the end of the period, we either convert, iterate, or stop. That discipline prevents wasted effort and forces both the vendor and the customer to treat the exercise seriously.

Implementation in this manner proved to shorten cycle time and which leads to increased product release velocity, in other words allow us to ship faster. Additionally, which is probably more important, engaging with customers before starting coding helped us to grow feature adoption, at least among key customers, which eventually led to a higher customer satisfaction rate.

Taken together, this framework (fast MVPs, early monetization, dual-track approach, and disciplined pilots) creates a way of working that aligns product teams with the demands of enterprise customers. It’s not about building the perfect product, it’s about building a successful product.

Conclusion

Building a SaaS product is never straightforward. It’s complex, often unpredictable, and full of moments where even the best-laid assumptions collapse under reality. But while uncertainty can’t be eliminated, it can be managed. The difference comes from having the right tools, frameworks, and discipline to navigate the unknown.

An idea on its own is exciting, but without a structured plan, it rarely survives the transition from concept to market. For me, that plan begins with the right people at the table, a clear scope of work, and documented, user persona-specific outcomes we can test and validate. Today, AI has made this process faster and more accessible by providing powerful tools for early validation, rapid prototyping, and user feedback at scale. Yet no amount of technology replaces the fundamentals. Every step - discovery, validation, scoping, execution - must still be done with rigor. The speed has changed, but the discipline remains essential.