I spent years believing that a green dashboard meant the product was healthy.

In late 2022, I walked into a Q4 planning session for a SaaS platform scaling toward $25 million in annual recurring revenue. I came prepared with what I thought was a bulletproof deck. Our Net Promoter Score (NPS) was at an all-time high of 75. Engineering velocity was at a record peak. Every major milestone on the roadmap had been delivered on time.

I expected approval. Instead, the CEO looked at the growth chart and asked a question that stopped the room.

"If the product is doing this well, why is our cost to serve increasing faster than our revenue?".

In that moment, I realized I was running a high-velocity feature factory with zero financial literacy. I was optimizing for sentiment and activity while ignoring the economics underneath the business. I could tell the room the latency of our API calls, but I could not tell them if the release was profitable.

As teams approach 2026 planning, the era of growth at all costs is over. The mandate has shifted to efficient growth. Product managers who want to survive the next budget cycle must stop acting like backlog administrators and start acting like portfolio managers.

Here are the three financial metrics that replaced velocity on my own scorecard.

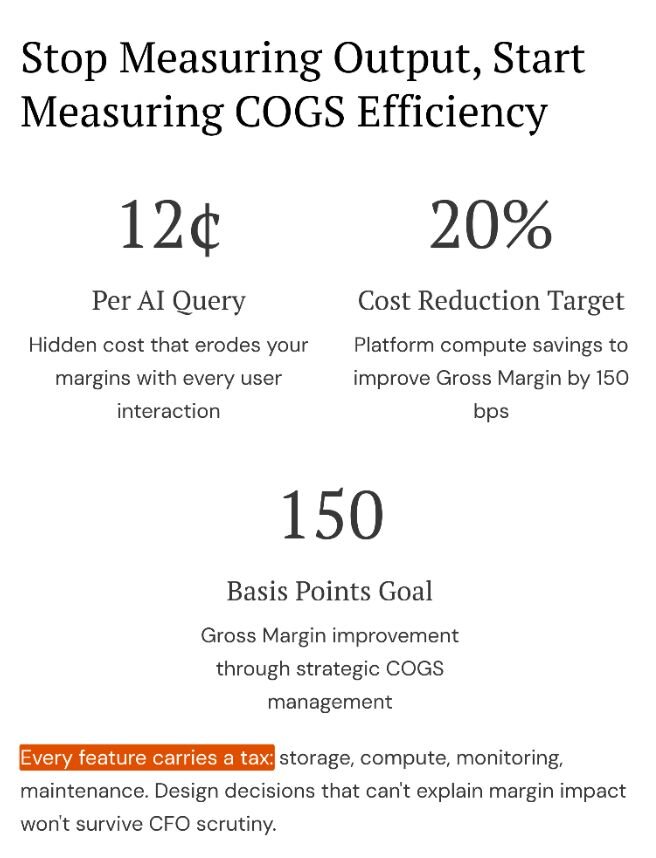

1. Stop measuring output, start measuring COGS efficiency

Every feature you ship in 2026 carries a tax. It adds database storage, compute load, monitoring, and long-term maintenance. Financially, this increases your Cost of Goods Sold (COGS).

Early in my career, I led a team that launched an AI-driven search experience. The release looked like a success. Engagement spiked. Internally, it was celebrated as technical progress. What we failed to model was the variable cost of the intelligence supply chain. Each natural language query consumed roughly twelve cents in inference tokens.

As usage grew, our gross margins shrank. We had built something users loved that quietly damaged the solvency of the business. We were effectively subsidizing our customers' search habits with our innovation budget.

From that point forward, COGS efficiency became a standing metric in our roadmap reviews. We stopped asking if we could build it and started asking if we could afford to win.

- The metric: Gross Margin basis points (bps)

- The 2026 goal: Reduce platform compute costs by 20 percent to improve Gross Margin by 150 bps

In 2026, design and engineering decisions that don't account for their own margin impact will be increasingly difficult to defend to a CFO.

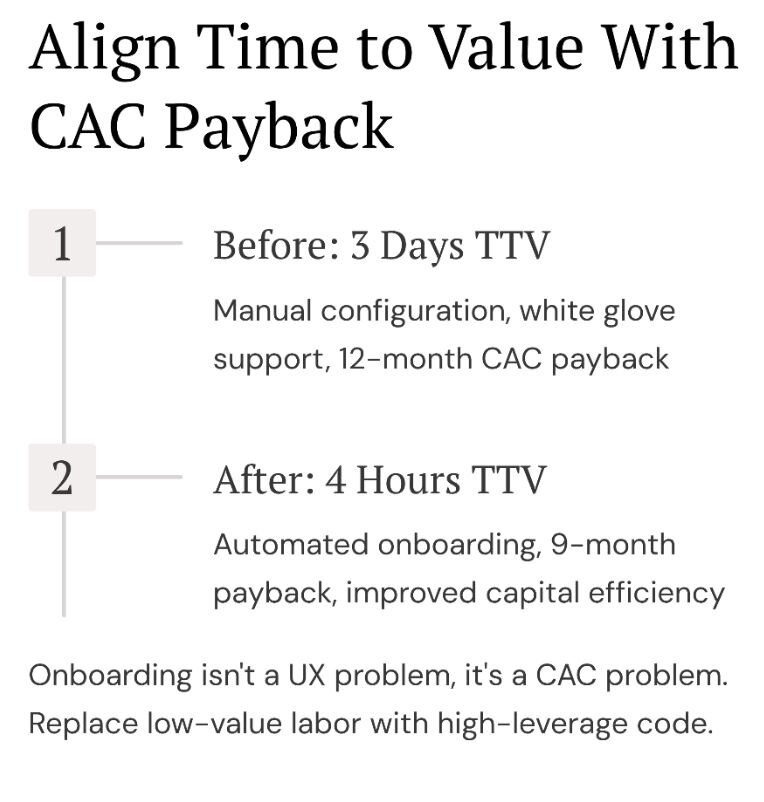

2. Align time to value with CAC payback

Most product teams treat onboarding as a user experience problem. It is actually a customer acquisition cost (CAC) problem.

In one role, our Time to Value (TTV) was three days. Customers needed seventy-two hours of manual configuration and "white glove" assistance before they saw their first report. To compensate for this friction, we poured resources into high-touch customer success and support teams.

Our CAC payback period, the time it takes for a customer to generate enough revenue to cover the cost of acquiring them, stretched to twelve months. We were spending so much on human labor to bridge the gap in our product's onboarding that we were barely breaking even.

By reframing onboarding as a financial constraint instead of a UX initiative, we prioritized automation over aesthetic polish. We looked for "low-value labor" and replaced it with "high-leverage code." That shift alone shaved months off our payback period.

- The metric: Time to Value (TTV)

- The 2026 goal: Reduce TTV from 3 days to 4 hours to lower CAC payback from 12 months to 9 months

In 2026, UX work that does not improve capital efficiency will increasingly lose prioritization battles to projects that protect the P&L.

3. The CapEx versus OpEx portfolio test

The most revealing metric I use today is whether engineering time is building assets or funding maintenance.

I recently audited a product organization that felt stuck. Leadership believed they were innovating aggressively. Their capacity data told a different story. Eighty percent of engineering hours were consumed by operating expenses (OpEx): maintaining legacy features, fixing edge cases for a single enterprise customer, and managing bespoke configurations that didn't scale.

Only twenty percent of capacity was available for true investment (CapEx). They were not an innovation engine. They were an expensive support desk.

We introduced a simple allocation review at quarterly planning. We treated our engineering capacity like a diversified investment portfolio. We identified "zombie features" that were consuming 40 percent of our budget while serving 5 percent of our users and we ruthlessly sunset them.

- The metric: R&D Allocation Ratio

- The 2026 goal: Shift from 70 percent OpEx to 40 percent OpEx to free capacity for innovation

You cannot fund new bets if yesterday's decisions consume all your capital. Stewardship means being just as disciplined about what you stop doing as what you start doing.

Conclusion: The product P&L

To level up in 2026, product managers must change the language they speak.

When you can explain how a roadmap decision improves Gross Margin, shortens CAC payback, or reallocates capital from maintenance to innovation, you stop being evaluated as a delivery lead. You start being trusted as a business owner.

Stop showing stakeholders a roadmap of tickets. Start showing them a roadmap of returns. That shift is how product managers move from the feature factory to the executive conversation.

Keep reading

Should product managers be responsible for a product revenue KPI?

Products on average retain 30% of customers after 3 months: Product benchmark findings

From conception to clarity: Navigating the KPI journey for product managers

Measuring the user experience by Tomer Sharon