MVP is a phrase that startup people love to throw around.

It’s an acronym that can be used as a weapon. Everyone believes their vision is really the Minimum Viable Product. You can use the phrase to batter your colleagues’ ideas. You can simply declare “it’s not really minimum” if you want to do something less than their vision, or declare “it’s not really viable” if you want to do more!

But MVP is a key concept in product management. It’s the first step to creating software that actually has value, and that’s what this business is all about. Completing a successful MVP is a wonderful feeling. You discover that there are people who actually want the thing you’ve been dreaming about.

Yet for all the chat about MVPs, many people have never felt the tug of a successful MVP. It’s like talking about fishing without ever having felt a bite.

What does a successful MVP feel like? 15 years ago we founded a product development studio, Mint Digital, and we’ve launched at least 100 MVPs since then. Most were crashing failures. Three successful ones stick in my mind.

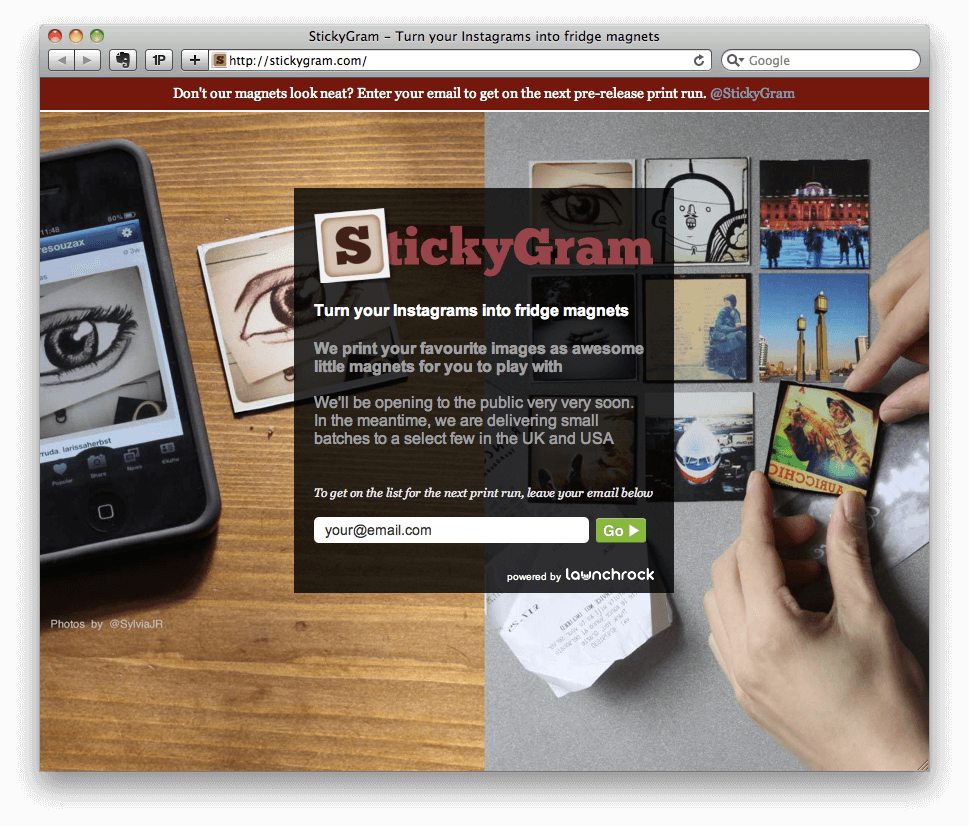

1. StickyGram

I had a talented colleague called Kejia Zhu who kept dreaming about fridge magnets personalised via Instagram.

On the sly, Kejia created a Launchrock sign-up page for his idea. A few days later he had 2,000 people signed up. This was back when the Instagram API was the new new thing, so fusing it with fusty old fridge magnets seemed brain-bendingly bananas.

2,000 signups from one rough mockup and a few tweets! That’s the tug of genuine market enthusiasm.

2. Boomf – Marshmallows

We sold StickyGram after a couple of years. Then we met a man who had developed the technology to personalise marshmallows. This concept split the team. Most people thought it was an atrocious idea. Others thought it merely stupid.

“Internal opinions should be disregarded with a degree of ruthlessness,” says Mo Khan, product manager at TransferWise. I wish I’d read that five years ago, as that’s what I was thinking but couldn’t articulate. I was convinced that personalised marshmallows were like Marmite. But I thought that even if 80% of the world hated the idea, as long as the other 20% liked it, we had a big market.

Because I was young and foolish, I rode roughshod over the objectors. We hacked together some photo manipulation and e-commerce software and launched it for Christmas.

Boomf got a loud reception. Everyone from TechCrunch to The Atlantic wrote about it.

Looking back, this was a bad MVP. It took four people three months to implement. There must have been a less costly way to bottom out the assumptions in the MVP.

To be fair, we had taken prototypes on the street and asked people for their reaction. Some people hated it. Some people said they liked it. But we didn’t have a good way to benchmark. How do you tell the difference between a polite yes and a genuine desire to buy? We didn’t know, so we rushed ahead with a big punt.

3. Boomf – Bomb

We did a much better MVP for the Boomf Bomb.

After our success with Boomf marshmallows, we launched a couple more products. Neither got any traction. We were a bit stuck.

Luckily we met the amazing Sophie Dummer, who had been a superstar at M&S – she invented the three for £10 knickers deal. (Who knew that even needed to be invented?) As an M&S veteran, she knew how to do things properly.

We had 12 half-completed new products in development. She said we had to show them to a focus group next week. Yikes! This whittled the 12 half-baked concepts down to five that were actually worth showing.

Of the five, there were two that we actually knew how to manufacture. Of the two, there was one that left us waving our hands explaining why we thought it was a good idea. And one that made the focus group’s eyes widen with enthusiasm. Bingo — that’s the reaction we are after!

Side Note: Does a Successful MVP Equal Product/Market Fit?

Not at all. A successful MVP shows you’ve got the tug of initial interest but it doesn’t show whether you can get your product to market.

These three examples all had different routes to market and each route took many months to discover. The MVPs didn’t offer any clues as to what the route to market would be. (I’d be happy to write about this too. If you are interested, please leave a comment below.)

What can we Learn?

Each MVP looked rather different. Were there any common threads?

1. The team shouldn’t be obsessed with data. You are looking for a feeling: a tug on the line. Startup teams tie themselves in knots considering how they’ll collect the right data from an MVP. This is wasted effort. You are looking for enthusiasm, not empirical proof.

Seek to build an MVP that evokes the emotion you seek in customers. You want to see prospective customers’ eyes widen in excitement (perhaps metaphorically, if the MVP doesn’t happen face-to-face).

2. Avoid the temptation to write software. It is so so tempting. It feels like real work. It articulates how the full vision will be delivered.

But building a piece of software that is good enough to test on users is a huge job. Slick software takes time. Unless the MVP is slick, users will struggle to get beyond “this is clunky”.

Remember, you are trying to evoke an emotion.

Building a cut-down version of the product is, by an order of magnitude, the most expensive way to do an MVP. Assuming you are sane, you’ll want to maximise your learning to cost ratio. Before you commit to a software-powered MVP, be utterly sure that there is no way to learn 10% as much via a non-software MVP.

“Create a landing page, drive some traffic, and see if it’s something people want. But the strange thing is that this advice is routinely ignored – even by seasoned entrepreneurs.” writes Dave Bailey. It’s reassuring to see it’s not just me who falls into this trap.

3. The three example MVPs are all completely different – and that’s how it should be. It is hard to find a way to test your key assumptions without building the whole product but it is a key job for a product manager.

If you are stuck, work through a list of example MVPs – concierge MVP, video MVP, etc, – until you find one that you can bend to your situation.

I’ve just finished a project that involved scoping an MVP for a technologically complex new product. With the CTO, we explored the MVP from every angle and concluded there was no way to test the concept without spending three months building a prototype. When we pitched the plan to the (very talented) CEO, quick-as-a-flash he pointed out a way that we could get 90% of the learning in 10% of the time. He was absolutely right. There was a good way to test for the tug on the line with building an app, we just hadn’t considered the problem from the right angle. So, if there’s a moral to this story, it is: keep looking for a way to reduce your MVP!

Comments 0